In wintertime hundreds of orcas swim into the Norwegian fjords. They are after the huge schools of herring. The whales in turn are followed by numerous nature lovers and photographers. And who really wants to experience the spectacle: it is allowed to snorkel with the animals in the crystal clear, but very cold water. But how do orcas actually react on these bobbing spectators?

Written by Chantal Denise Pagel / October 2016

When hearing about orca watching, most people think of the Pacific Northwest, not knowing that Norway is probably offering the best opportunities for avid whale watchers within Europe. Especially the months November till February are ‘whale season’ in the area between Andøya and Tromsø, when hundreds of killer whales gather to feed collectively on the highly abundant herring, often joined by humpback and fin whales to participate in the feast. The spring-spawning herring (Culpea harengus) is entering the northern fjords in the winter months making this spectacle possible. In the recent years, the animals migrated from Tysfjord and Vestfjord to the waters of Norway’s second largest island, Senja. The small village Hamn is one of the places that welcomes tourists from all over the world to enjoy birdlife, the northern lights and especially the whales that can often be found just a few minutes outside the harbour. For my own field work I conducted in January 2015 I was able to witness the wonders of the Arctic North myself, investigating a new type of adventure tourism in the marine environment.

Only in Norway

Besides orca watching, Norway is offering a one-of-a-kind opportunity to those who are brave enough to face the cold air and water temperatures: It is the only place in the world where swim-with programmes (SWPs) with wild orcas are being conducted legally. SWPs, in which humans enter the water in order to watch and to interact with wild whales and dolphins, are experiencing an increasing popularity among tourists worldwide. Operations targeting wild orcas are practicable especially due to the absence of any legally binding regulations and restrictions in Norway as opposed to other orca home ranges and cetacean watching hotspots, such as the coastal habitats of the Pacific Northwest, where Marine Mammal Protection Regulations prohibit such activities.

Besides orca watching, Norway is offering a one-of-a-kind opportunity to those who are brave enough to face the cold air and water temperatures: It is the only place in the world where swim-with programmes (SWPs) with wild orcas are being conducted legally. SWPs, in which humans enter the water in order to watch and to interact with wild whales and dolphins, are experiencing an increasing popularity among tourists worldwide. Operations targeting wild orcas are practicable especially due to the absence of any legally binding regulations and restrictions in Norway as opposed to other orca home ranges and cetacean watching hotspots, such as the coastal habitats of the Pacific Northwest, where Marine Mammal Protection Regulations prohibit such activities.

Go big or go home!

Although ‘orca safaris’ in Norway already started in the early 1990’s, operations to enable in-water encounters with the orcas are a relative new phenomenon as mentioned by Damsgård in 2000 and which I have picked up as a research project. I wanted to find out how orcas interact with human divers and snorkelers, if they show any kind of aggressive behaviour with people actually being at risk during this type of wildlife watching. For this, I evaluated video material showing in-water encounters in Norway, being collected by professional filmmakers in Tysfjord, Vestfjord and around Hamn during the past 15 years. In addition, to get a personal impression of the operations and to collect own footage, I travelled to Hamn, facing icy cold air and water temperatures as well as hail storms from all directions. During the two and a half weeks, I was freezing. Permanently. Although I felt well equipped with a ski mask, a warm overall and the warmest gloves I could find, I’ve probably never felt so cold my entire life (with even hot showers for 30 minutes not really changing anything). Not surprising, it was hard for me to actually picture myself in the Arctic Ocean that has a constant temperature of 3 degrees Celsius (which is pretty warm considering local air temperatures of minus 15 Celsius…) and, of course, the feeding frenzy of orcas and humpbacks, with the latter really making me nervous since you never know where they are emerging. They are really good in disappearing for several minutes just to breaking through the surface with their jaws wide open, catching as much herring as possible. And when that happens, you do not want to find yourself in between! But this is what you do for science. You go big or you go home!

Snorkelers in the water with orcas. (Photo: © Annemieke Podt)

Rewarding moments

I decided to go not that big and stayed aboard when the animals showed hunting behaviour with subsequent feeding. Professional filmmakers tend to be more courageous since this is probably the most spectacular footage you can get. However, being a scientist is also about knowing your personal limits and so I spent some time in the small dinghy that was dragged behind the boat with humpbacks to the left and orcas right behind me with the daylight slowly fading out. In the end, this is what is left. I never felt more connected to nature and the animals, being worth all the freezing and struggling to get the data I needed. Those are the rewarding moments of being a conservation biologist. I was struck with awe which helped me to develop a study of high quality and the hope that it may contribute to the preservation of this pristine area, still being far away from mass tourism.

“Professional filmmakers tend to be more courageous since this is probably the most spectacular footage you can get.”

The participant’s responsibility

However, during the last year, Hamn and its whales received a lot of reputation through known wildlife photographers and filmmakers who amaze with spectacular images and close-up video material of the impressive protagonists, going viral in social media attracting more and more visitors to the small area. “I personally feel that the buck stops with the operators and especially with underwater filmmakers and photographers who rarely know their limits,” said Sven Gust from renowned whale-watching company Northern Explorers. From my point of view, it is important to educate tourists who seek to interact with the animals in their natural environment about the occurrence of potential behavioural patterns. The application of a code of conduct is a critical part of the management of SWPs, especially when legally binding regulations are lacking. It has to become clear that, although there has virtually never been an incident with wild orcas so far, these are highly specialised predators which need to be treated with respect that is also criticized by Sven Gust from Northern Explorers stating that it is the participant’s responsibility to avoid these risks and that a security of 100% can never be given.

This is the reason why so many people want to snorkel with orcas in Norway. (Photo: © Uli Kunz)

Environmental education and interpretation

Operators should have a broad knowledge of cetacean behaviour and ecology being imparted to tour participants. In general, tourist expectations should not be underestimated. During my fieldwork I overheard a conversation between two German tourists who apparently were disappointed about the whales not showing any active surface behaviour (= spectacular leaping) during their whale watching trip. Since this is shown on brochures, websites and wildlife documentaries. I was asking myself: ‘How can you be disappointed being almost alone with the whales, watching them feeding and resting in their natural environment within this outstanding scenery?’ But apparently there was something lacking. And it probably was entertainment, which made me really sad. The tourists did not see what I have seen. They were blind for the beauty of what I consider to be nature at its best. Because they expected something different and probably because they were not aware that wild animals cannot be compared with animals in a marine park. This example highlights the necessity of environmental education and interpretation before tourists get on board of whale watching boats and it is without doubt that this should also be in the interest of commercial operators as in the end tourist satisfaction is determining the future of such tours.

“How can you be disappointed being almost alone with the whales, watching them feeding and resting in their natural environment within this outstanding scenery?”

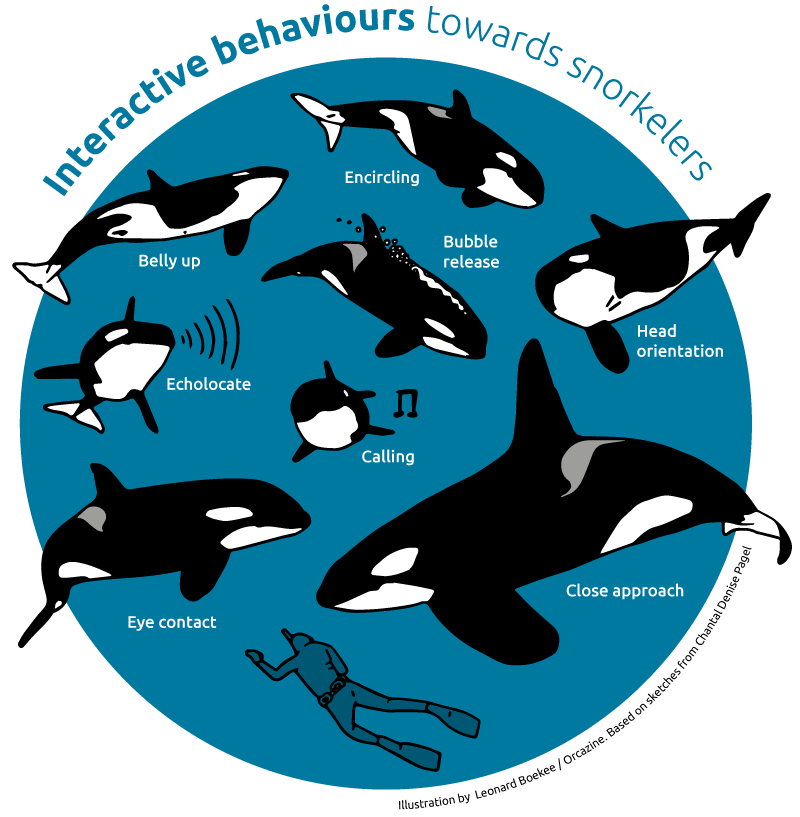

Eight interactive behaviour patterns

Regarding the results of my research, Norwegian killer whales seem to be very receptive for encounters with humans as eight interactive behaviour patterns (e.g. eye contact) were identified. Simultaneously, it has to be acknowledged that the interest in close interactions with swimmers is strongly dependent on the animals’ behaviour on the particular, and no guarantee for close encounters can be given at any time. People who come to Norway planning to swim with the humpback and killer whales were mostly identified as professional or semi-professional photographers and filmmakers who face the cold water and air temperatures to get spectacular footage.

However, despite a slightly different motivation to enter the water, certainly this kind of wildlife tourist needs to hold an understanding of how cetacean behaviour has to be interpreted and what kind of behaviour can be expected, in order to engage into safe and successful encounters with marine apex predators. The management of tourist behaviour is a critical aspect for safety in wildlife tourism. Topic-related literature has furnished the evidence that aggressive behaviour towards humans displayed by free-ranging cetaceans is often a result of swimmers seeking physical contact with the animal. That also was not performed during this study explaining the absence of non-threatening behaviour like an open mouth or jerky head movements. However, I want to emphasize that there is always a certain risk that never can be fully eliminated when interacting with wildlife.

Privilege

Therefore, from my point of view, interpretational programs should be obligatory for those who seek close contact with the animals. There is a need for experienced and skilled guides who are able to pass on their knowledge to tour participants in order to make the most out of this experience. We need to understand that we, as visitors, are highly privileged and should act accordingly that no matter how often we return we will always be welcomed with open flippers and a cheerful whistle!

About the author:

Chantal is a double-degree conservation biologist from Germany who specialised in marine wildlife tourism, with focus on whale watching and interactions between humans and cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises). Her Master thesis dealt with interactive behaviour of Norwegian killer whales (also known as orcas) towards human snorkelers and divers and provided first insights into a tourism practice that is worldwide unique. From sperm whales to Galapagos sharks she encountered various marine species herself and is currently preparing her admission to a doctoral programme that will address risk management of close encounters with marine wildlife in open-water environments.

Chantal is a double-degree conservation biologist from Germany who specialised in marine wildlife tourism, with focus on whale watching and interactions between humans and cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises). Her Master thesis dealt with interactive behaviour of Norwegian killer whales (also known as orcas) towards human snorkelers and divers and provided first insights into a tourism practice that is worldwide unique. From sperm whales to Galapagos sharks she encountered various marine species herself and is currently preparing her admission to a doctoral programme that will address risk management of close encounters with marine wildlife in open-water environments.

Nederlands

Nederlands